By the end of the 1990s, the Internet revolution had not only transformed the medium of communication but had also turned into a whole new business paradigm. As the dot-com bubble was reaching its peak, the digitization of everything led to a frenzy among investors, who saw the potential of the digital world, and therefore of the tech sector and disregarded the risk, the venture capital persons also lowered their requirements, as the VCs were in a mood of de-risking, and companies having just an internet address were valuable to the maximum. Little did it know that this was only the beginning of the end.

The era of the “dot com boom” saw spectacular gains turn gigantic losses, not seen before in the history of financial markets, and experienced a bloodbath that drained the immense wealth of numerous individuals and devastated the area which later became known as Silicon Valley definitive of the dot com bubble and why this occurrence has remained one of the seminal incidents in the history of the financial industry. Now that the answer to “what was the dot-com bubble?” has been fully explained, we believe that you realize why it is often referred to as the greatest lesson to be learned from the field of finance.

The Early Sparks: How the Internet Captured Wall Street’s Imagination

The internet began to garner attention from business entities during the early 1990s—this was the same period when other aspects of technology, such as computing, telecommunications, and software, were also being improved. The rapidly growing internet accessibility of homes and businesses was being realized across the world making everyone aware of the internet’s functionality.

Internet development and use were gathering momentum; Netscape, Yahoo!, and AOL led the way with their services that captured many users and the attention of many venture capitalists. The rapid increase in the number of start-ups became possible due to their initial success. The only thing they were interested in was the Internet-related stuff, e.ge, commerce, content delivery, and search engines. And everything was judged by “.com” – the more modern-looking, the more wealth-coined one was.

Investors, with the opportunity to be early supporters of a new industrial revolution, were the ones who started to inject their money into the internet startups. Traditional parameters, such as revenue and profit, became irrelevant, rather the ability of a business to grow its users and to be recognized as a brand was favored. This disruption was the basis of a gigantic bubble formation in valuation which was not sustainable.

IPO Frenzy and the Birth of the Bubble

Between 1997 and 2000, the Nasdaq index was the center of a technology stocks buying craze. Every month a large number of brand-new companies were offered to the public, while most of them had no sales, no earnings, and no business models at all. Still, their share prices skyrocketed, a lot of times they did double or triple on the very first day of trading.

In the year 1999 alonei, internet companies accounted for almost 40% of venture capital investments. At the same time, there were 457 IPOs, which primarily belonged to the tech sector. The investors were afraid of losing the chance of getting a stake in the next Amazon or eBay, so they took advantage of every situation.

The apogee of the mania was the January 2000 merger of AOL and Time Warner, of $164 billion. This transaction is now considered one of the most outrageous in the annals of the business world, but it spelled out the degree of absurdity of the valuations that had been made.

The Role of Venture Capital and Easy Money

An important factor in the emergence of the bubble was the availability of venture capital and the cheapness of loans. At that time, the interest rate was low, and venture capitalists were pursuing a high return amidst the calm. Companies that added a “.com” suffix to their names were able to close multi-million-dollar, venture capital-funded deals with hardly any control or performance indicators.

Companies that were able to get the money from venture capitalists have only one purpose to spend it as soon as possible not through product development but through marketing and user acquisition. Some companies even put aside up to 90% of their budgets for the purpose of advertising, principally during high-profile events such as the Super Bowl. They were not engaging in sustainable business practices; instead, they were generating buzz.

This marketing-heavy strategy was justified by the idea that the Internet was a winner-takes-all system—get the market share fast, worry about the profits later.

Valuations Detached from Reality

Things got to the point when conventional investing concepts, let’s say, price-to-earnings ratios, no longer applied during the bubble time. Most of these young companies with no income reached the valuation of hundreds of millions or even billions. Many companies went public, the majority of them without a developed product, not to mention tapath to profitability.

The confidence of an investor was presented not so much by concrete results but by the sentiment. Media coverage, showy press releases, and the presence of charismatic founders all together fueled the sentiment that created a cycle of optimism, investment, and valuation increase.

It was a classic feedback loop: soaring stock prices triggered an increase in media attention, which in turn attracted more investors, driving prices even higher. The phrase “dot-com bubble” was nothing but a later reflection of the same economic development.

Cracks Begin to Show

It was not long before 2000 thatt the whole world spotted the frailties of the Internet economy. The market was shaken by a few eves ,such as a few famous tech firms’ earnings misses and profit warnings like Dell and Cisco that startled investors. Even these relatively stable companies did not quite correspond to that image, offloading large amounts of stock and thus provoking the concern that such insiders cashed in.

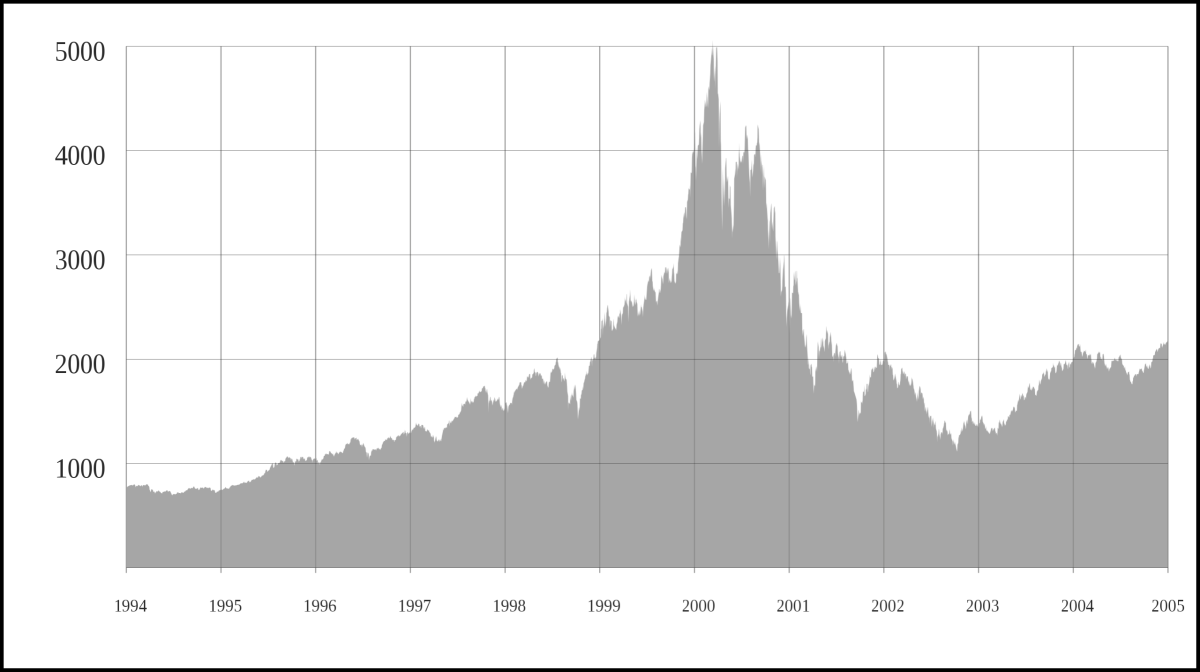

The Nasdaq registered a new record high of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000. Then, the sales got worse. In the next 24 months, the index plunged to nearly a quarter of its value, which was 1,139.90 in October 2002.

Not only investors’ on-paper profits were gone, but the dotcom collapse also caused many companies to file Chapter 11, burned retirement accounts, which were the main income for many people, and the whole tech investing business model was redefined.

The Great Collapse: Dotcoms Go Dark

As capital was exhausted, so were the lives of these startups. The phrase “burn rate” became notorious for denoting how rapidly companies were expending their cash. The end came quickly, as without a consistent income to run their businesses and without getting new funding rounds, they shut down.

By the end of 2001, almost all internet companies that were traded on the public market were no longer in existence the majority of their business. Once-appealing startups such as Pets.com, Webvan, and eToys had become mere memories. According to analysts, investors were nearly $5 trillion poorer in the market.

Well-known tech companies also had to bear the brunt. Stocks such as Cisco, Intel, and Oracle fell by a whopping 80% in value. The “dotcom crash” was not just some simple market adjustment—it was more of a financial crisis outbreak.

Survivors and Silver Linings

Despite a significant percentage of the companies that went out of business, there were still some that rose to the next level. Amazon, though slightly injured, managed to ride through the storm mainly through cost-effective operations and client retention. eBay carried on with the expansion of its customer base and a steady upward swing in the sales revenues. Priceline, on the other hand, underwent a facelift and diversified its business model. All these companies conversed quite understandably about having real income and scale models.

The wreckage also served as an important learning event. Investors turned into a cautious lot. The venture capital ecosystem has become more mature. It was the time of “growth at all costs,” which was replaced by a renewed focus on profitability and sustainability.

On the other hand, the infrastructure put up during the bubble years—broadband access, data centers, e-commerce systems—cleared the road for the next wave of tech growth in the 2010s.

Rethinking Risk: Financial and Cultural Impact

The dotcom era not only changed the way of living but also the financial landscape in Silicon Valley and Wall Street. It provided both retail and institutional investors with lessons on how dangerous speculation can be, how important due diligence is, and the negative consequences of chasing trends.

In response, the regulatory bodies also did. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 was a reaction that introduced more rigid corporate governance and accountability standards. There was a stricter regime for analysts and underwriters for biased IPO recommendations and misleading financial disclosures.

Furthermore, even the way tech entrepreneurs marketed their businesses had undergone changes. The primary focus was now on monetization strategies and real metrics instead of vague potential.

The Tech Renaissance That Followed

With hindsight, it’s certain that the internet wasn’t massed up—it was simply encashed early. Many of the business models that were unsuccessful in the dotcom era survived until technology was sufficient. Streaming, online advertising, social networking, cloud computing—all had their sources in late 1990s.

Today’s tech giants, such as Google, Facebook, and YouTube, were able to come to existence due to, to some extent, the infrastructure and experimentation of the bubble years. The wrong ideas were not necessarily terrible; they were just poorly timed and overfunded.

So if one still didn’t get the answer to the question ‘what is a dot com bubble,’ he was indeed asking about the way the technical revolution managed to establish without despite all these miscalculations, abuses, and bitter experiences.

Timeline Recap: Key Events of the Bubble

- 1995: Netscape IPO sets off public internet excitement.

- 1997-1999: Venture capital was lavishly poured into the market, and “.com” IPOs experienced a well-nigh vertical rise.

- Jan 2000: AOL is merging with Time Warner.

- Mar 2000: Nasdaq reached its highest 5at 048.62.

- Mid-2000s: Major technology companies begin to release shares.

- 2001-2002: There is a wave of bankruptcies in startups; Nasdaq collapses by almost 80%.

- Post-2002: Surviving firms appear; new laws are introduced for regulation.

Comparing Then and Now

The dotcom bubble still serves as a fitting analogy for other present-day financial happenings. Be it digital currencies, SPACs, or EV startups, the early years of the 2000s were full of lessons that are still applicable. There is no denying that hype is significant, but businesses should not overlook the fundamental facts. As it was back in the ‘dot-com boom days,’ the investors of today are generally in need of time and space to distinguish between the ideas that have great potential and the fads of short duration.

A crucial point is that the internet of today is powered by businesses with sustainable revenue models, enormous user bases, and well-proven platforms. This was not the case in 1999. However, the present generation of investors and entrepreneurs has learned a substantial amount from the mistakes of the past, and they are therefore more circumspect when it comes to risks.

Conclusion: What Was the Dot Com Bubble—A Lesson Still Relevant Today

Vivid understanding of “what was the dot com bubble” enables us to comprehend that it was not only a financial anomaly. It was a period where the hype drove out the rational part of strategy and innovation was moving faster than the infrastructure, and the belief in the internet’s promise was the main reason why many people could not see reality anymore.

The “dot com” frenzy brought down a considerable number of companies and led to many investors losing their money with failed businesses but it also kindled the process of digital transformation that we still live in. It marked the danger of getting carried away with the promotion at the same time signifying that growth that lasts is the most critical element.

Learning how the “dot-com bubble” transpired and vanished is not limited to uncovering facts from the past. The whole story of it includes valuable lessons for today’s tech stocks and emerging technologies, i.e., the behavior of investors, market cycles, and the economic condition basics are quite the similar factors.

Thus, in querying “what was the dot-com bubble”, a cautionary story is not the only thing we reveal to ourselves, but a moment of the digital economy’s history is being built.